On Love, Madness, and Gender in Fiction

In the tales we inherit, the stories we are raised on, and the cinema that hits our screens, love is rarely ordinary. Where it is not measured in steady companionship or quiet intimacy. No — love, as media so often portrays it, must be catastrophic. It must wreck and ruin, consume and transcend. To love is to fall, and to fall is to burn. But whose ashes are honored? Whose descent is permitted — even celebrated — as divine?

From ancient legends to modern love stories, male madness is often romanticized. The glorification of man’s passion/destruction. It is elevated to the realm of poetry, of sacred torment. Women, on the other hand, are rarely afforded this narrative grace. Think Ophelia in Hamlet, or Laila in the film Laila Majnu, whose pain is subdued, quiet, or erased.

“Male heartbreak in film is often a public spectacle, drenched in music and grand gestures, while female heartbreak is expected to be private and dignified—often invisible. This disparity reflects deeply entrenched gender norms.” — Sadie Doyle, in Trainwreck: The Women We Love to Hate, Mock, and Fear... and Why (2016)

Madness as a Stage of Love: The Male Lover’s Divine Right

In literary and cinematic history, male lovers are frequently portrayed as saints of sorrow — their descent into madness framed as the pinnacle of devotion. From Qais turning into Majnu, to Devdas losing himself in alcohol, madness becomes a performance of masculine vulnerability, and thus, of spiritual greatness.

Laila Majnu, which has travelled centuries and continents — from Nizami’s 12th-century Persian romance to Bollywood’s 2018 cinematic reimagining — tells us of Qais, the young lover driven to madness by his unfulfilled love for Laila. His transformation into Majnu — meaning madman — is not a descent into despair, but an ascent into spiritual martyrdom. The desert he wanders becomes holy ground; his hallucinations, prayers. He is praised for his madness, immortalized in folklore as the lover whose devotion defied reason.

But Laila? Laila is not given that same space to fall apart. Her suffering is real, but it must remain silent, sealed in duty, in marriage, in sacrifice. She is not allowed to scream, to unravel, to lose herself in the same way. Her pain is aestheticized, contained. The woman’s burden in love is endurance, not expression.

“So many stories glorify the boy’s descent into madness or self-destruction for love, but the girl’s experience remains a subplot, her pain muted, her agency erased.” — Molly Ringwald, paraphrased from her 2018 New Yorker essay, “What About ‘The Breakfast Club’? Revisiting the Movies of My Youth”

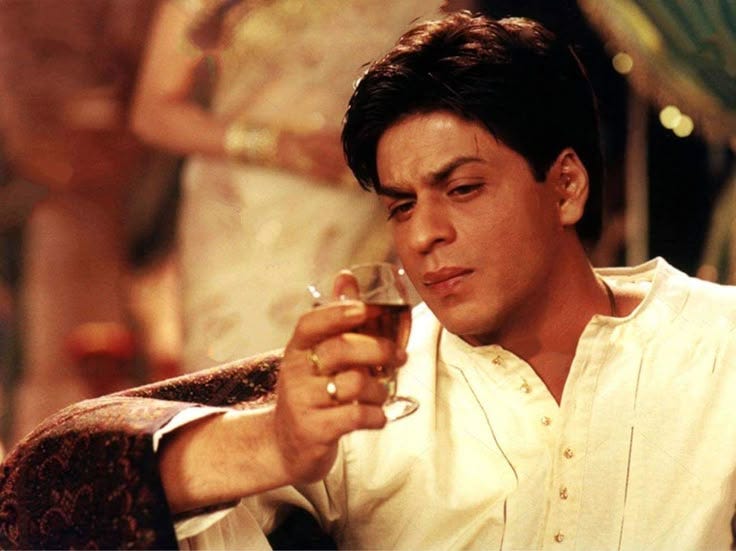

This is no isolated pattern. Again and again, media turns the tortured male lover into a tragic hero. Devdas, perhaps the most iconic example in Indian literature and cinema. In Sarat Chandra Chattopadhyay’s 1917 novel and its many adaptations — particularly the grand 2002 version starring Shah Rukh Khan — Devdas drinks himself into an early grave, mourning his lost love Paro. His alcoholism, his recklessness, even his self-pity are portrayed not as weaknesses, but as signs of profound feeling. He dies at her doorstep, and the moment is immortalized as romantic sacrifice.

Meanwhile she is forced into a loveless marriage, expected to uphold her familial duties, and spends the rest of her life behind the bars of a wealthy home, dignified in her restraint. She loves, but she must do so with decorum. Her passion is muted, disciplined, and, ultimately, erased. But we are taught that his suffering means more. Her love is discipline; his love is destruction. But destruction, we’re told, is deeper.

“The narrative of Devdas glorifies male self-destruction while women are relegated to archetypes of patience and sacrifice. It’s a story about a man’s torment, not a shared human tragedy.” — Shashi Tharoor, paraphrased from a 2018 panel discussion on literature and gender

This trope continues in contemporary storytelling. Kabir Singh (2019) resurrects the archetype of the male lover whose rage and self-destruction are justified — even glorified — by his heartbreak. Kabir is violent, obsessive, and emotionally unstable. Yet the narrative asks us to see him as a man undone by love, as if brutality were a proof of depth. Preeti, the woman he claims to love, is rendered passive, voiceless, and disturbingly submissive. She exists not as a character, but as a reward for his suffering.

“The Manic Pixie Dream Girl exists solely to inspire the male protagonist’s growth; she is not a person with her own desires or struggles. This trope denies women complexity and reduces their emotional lives to plot devices.” — Gina Barreca, feminist scholar, University of Connecticut

What these stories teach us — implicitly and explicitly — is that to be a man in love is to be allowed madness. It is to scream, to grieve, to destroy, and still be seen as noble. Male pain is validated; male breakdowns become art. A man’s suffering, in these tales, deepens his character. A woman’s suffering simply diminishes her.

Madness becomes the male lover’s second skin, a transformation he earns through emotional excess. He is allowed — even expected — to lose control, because that loss itself becomes an artistic triumph.

Death as the Destination of True Love: The Romanticization of Ruin

Love, in art, often ends not in healing, but in death. And for the male lover, death is not failure. It is transcendence.

In Aashiqui 2 — India’s A Star Is Born — Rahul’s suicide is the ultimate sacrifice, the completion of his character arc. Aarohi, the woman, survives — her grief made noble by the quiet way she carries it.

This pattern reveals a chilling truth: in fiction, for men, death is a canvas. For women, it is erasure.

Why, then, are women denied the right to romantic ruin? Perhaps because it is dangerous. A woman who rages is a woman who resists. A woman who is allowed to go mad for love might become too visible, too demanding. She might take up too much space. And history has taught women to shrink.

“When women sing about sadness or obsession, they’re called ‘dramatic’ or ‘crazy.’ Men get to be tortured poets.” — Paraphrased from various interviews with female musicians and critics, incl. Taylor Swift and Fiona Apple

The Silencing of Women: The Expectation of Emotional Grace

Where male pain is centered, women are often reduced to symbols of stoic suffering. Their love must be patient. Their heartbreak, invisible. When women express agony, they are pathologized: “hysterical,” “obsessive,” “over-emotional.”

Ophelia in Hamlet is a prime example. Her descent into madness, unlike Hamlet’s, is stripped of poetry. She sings nonsensical songs, drowns with flowers in her hands. Her pain is not philosophical — it is weakness. Her madness is a side effect of loving too much, of being too fragile. Hamlet’s, on the other hand, is a sign of his intellect, his moral struggle with justice and revenge.

Similarly, in Kabir Singh, Preeti has no room to express anything. Kabir explodes, destroys his life, screams and slaps and spirals. She, meanwhile, speaks in whispers. Her emotional stillness is mistaken for grace — but it is just a lack of space. The narrative offers her no agency, no breakdown, no flame.

“Love in patriarchal culture is often defined by power, control, and sacrifice — especially sacrifice from women. The romantic ideal frequently romanticizes male suffering but expects female silence and endurance.” — bell hooks, All About Love: New Visions (2000)

The narratives we consume shape our understanding of love — of what it means to feel, to fall, to lose. And when only one gender is allowed to descend into madness, it subtly tells us whose feelings are worth remembering. In many ways, as women we are told not to take up space.

But fiction has the power to reimagine. To rewrite. We need stories where women, too, are allowed to fracture — not silently, not prettily, but completely. Where their love is messy and fierce, their heartbreak unrestrained. Where they are not just the muse or the martyr, but the mad one — holy in her hysteria, sacred in her sorrow.

And there lives a dream— of a cinema where Laila screams into the night, where Paro throws the liquor bottle back, where Ophelia walks out of the river. Let us write the women who refuse to stay quiet in their grief. Women who don’t just remain there like footnotes. Women who take up as much space as they want. Let us give them the right to descend — and to be believed, not broken.

Until then, the deserts will remain haunted by Majnus, wandering in search of something women were never allowed to lose.

thank you god for creating smart & articulate women

"And when only one gender is allowed to descend into madness, it subtly tells us whose feelings are worth remembering." 👏🏼👏🏼👏🏼

This was absolutely beautiful and translates well into real life. It reminds me of why I'd rather die than live like my female ancestors— head bowed and silently enduring all the mental load while an angry man leads the household.

This is also why I yearn for more movies like MaXXXine and Pearl. I want to see more women unapologetically erupting with unbridled rage and grief.